The Prestige Trap

The Employee Factory III: The danger of measuring our self-worth and how it leads to materialism

In the first two installments of The Employee Factory (1, 2), I discuss how schools are becoming increasingly utilitarian and failing to create students that become fulfilled later in life. It’s not crucial to read these to understand this installment, but it would make my ideas clearer.

How could they see anything but the shadows if they were never allowed to move their head?

This is from Plato’s “Allegory of the Cave”. The story begins with prisoners who have lived their entire lives chained to a wall inside of a cave. Behind the wall is a fire, and between the wall and the fire, there are people carrying puppets and other objects. The prisoners watch the wall directly in front of them as shadows from the objects behind them are cast. The shadows are reality to the prisoners, as they have never known anything else.

Plato continues by proposing that one prisoner could somehow become free. This prisoner gets away from the cave, and in the process realizes that the shadows are not reality. After entering the real world, they would be temporarily blinded by the brightness of the sun. But eventually, the escaped prisoner would appreciate the outside world and try to free the other prisoners.

Upon arriving back in the cave, he would be blinded because his eyes became accustomed to actual sunlight. The prisoners would see his blindness and believe they will be harmed if they try to leave the cave. The escaped’s efforts to free the other prisoners would be futile.

This allegory has been repurposed through notable movies such as The Truman Show, The Matrix, and Interstellar, among others.

But why is it relevant to the education system?

Let’s look back at the quote. The shadows convey reality, and they’re controlled by somebody else — whether intents are malicious is irrelevant here. Prisoners aren’t allowed to move their heads in the cave, but for our purpose let’s edit it a bit and say “they were never [taught] to move their head”.

In the first installment of the series, I use Socrates to explain how conversational learning opens the door to independent thought and criticize the lack of it in our schools currently.

When students aren’t taught how to think independently, how can they find fulfillment, an intrinsically unique feeling? Instead, they follow the group, who follows the leader, and students are left empty-handed, as discussed in the second installment. Does this sound familiar to the escaped prisoner returning to the cave only to be rejected?

What do you get when you combine the incapability of independent thought with a groupthink environment?

The prestige trap.

The trap is initially laid during the early schooling years. Students are measured via grades and disciplinary records. From here, they’re praised or reprimanded accordingly. Through positive feedback loops of praise, they’re affirmed in getting good grades. They think “hmm, well an A would make me feel better about myself than a B” which eventually turns into “well, that guy over there with the Cs, I must be better than them because I’ve received more praise”. Obviously, the thoughts wouldn’t be as explicit as this, but even if they’re subliminal they’re still there.

This transpires due to the effect grades can have on self-esteem and how they take part in building self-image. The problem isn’t that they’re being praised, it’s that praise is offered for results rather than for actually learning the information.

Eventually, students internalize that the ends are more important than the means. From this, ends can be measured, with certain things put above others on a narrow, non-negotiable scale.

For example, “CS is a better major than English since it has a higher average salary after graduating”. Using the same results-based style of evaluation used by sports fans, “MJ is better than Lebron because he three-peated twice!”, ignoring that all successes require multiple factors.

But this is only valid if the assumed primary driver of what makes somebody happy is measurable and applicable to everybody. This, as discussed in the last piece, isn’t always true due to fulfillment’s unique requirements for each brave individual chasing it.

This happens because students are not taught how to independently think with the shadows cast by their parents, teachers, and peers. In other words, they’re ineffective at judging what is best for their unique self.

But, whether the student has truly fallen into the trap isn’t shown until they have to make a few key decisions. The first is where they choose to attend college.

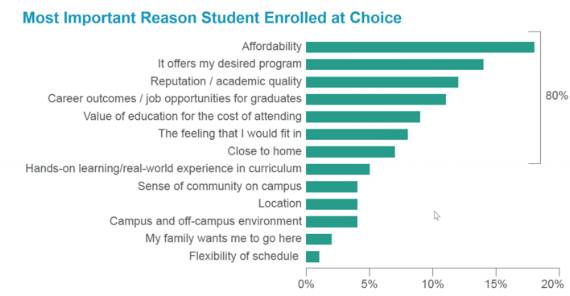

Consider results from Eduventures Research’s annual Survey of Admitted Students:

Notice how four of the top five most important reasons respondents chose their school are directly measurable (affordability, reputation, outcomes, value of education).

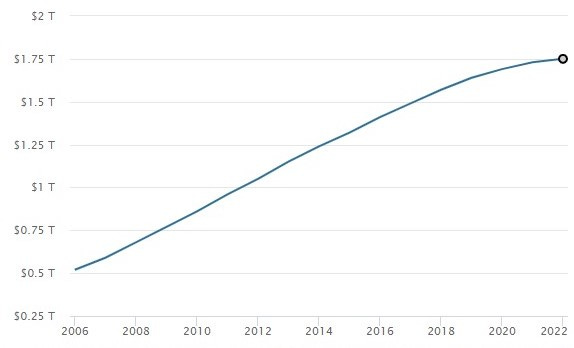

At first glance, it may seem that students are putting a heavy emphasis on affordability. While it was the most chosen, it’s still only 18% of total respondents, only 6% more than those who prioritized reputation and 7% more than outcomes. This is reflected in the total amount of student loan debt in the US from 2006-2022:

This total works out to about $37,787 per loanee. Although, over 600,000 borrowers in the US are over $200,000 in student debt.

To fall into the prestige trap is to put yourself in heavy debt by placing too much emphasis on a school’s prestige or job opportunities. In other words, assuming these factors will outweigh the debt somehow. There are a couple of reasons why this can happen. First is an overestimation of how influential a marginally more reputable, but more expensive school can be in regard to future prospects. The second is through social pressures. I’m sure anybody here who attended college knew some people who put themselves into debt so they could tell their peers they were going to a better school. Or those who put themselves into debt to not be embarrassed by the school they would attend. It’s unfairly hard for an 18-year-old to not feel pressured by their lifelong peers.

Although it’s not as common as it once was, students can still recover from the trap during their university years. They can learn to prioritize their unique needs and follow their interests. Then they can escape from the trap assuming they didn’t slaughter themselves with an unholy amount of debt.

But, the end of college also provides the most dangerous route of falling into the prestige trap — choosing a first job.

It’s a fork-in-the-road choice, especially in a world of specialization paired with tight labor markets, making it hard to change course post-grad.

Consider the time requirements of a 9-5 job (even though 41% of full-time employees work more than that). Given this basic hourly structure, roughly 24% of the total time during working years is spent at work. This number varies per source, with one survey saying that as much as one-third of the average person’s life is spent at work.

Suggesting that a person’s job can have substantial effects on their happiness and path to fulfillment. If someone is spending 24% of their hours somewhere that makes them unhappy, that would certainly carry over to the rest of their life. But there’s no one-size-fits-all, no single job can be proven to make everybody happy.

It’s not even just about avoiding unhappiness, finding happiness in work can also increase productivity by as much as 12% as found by researchers at the University of Warwick. This could lead to increased achievements at work and heightened satisfaction via promotions, those coupled with pay raises of course.

Yet, picking the right job becomes difficult when students have been measuring themselves against others to find happiness rather than examining their individual requirements for fulfillment.

Of course, the first step to choosing a job is to choose a major. BestColleges has a few primary suggestions:

Before you commit to a major, you should consider several factors, including the program cost, your salary expectations, and the employment rates in that field of study. In addition, you should think about your personality, your academic and professional goals, and your interests.

This is overall a balanced and reasonable suggestion. But is this advocation of balance evident given major choices among current students?

Consider IPEDS data on degree volumes:

There’s a clear dropoff post ‘08 in humanities degrees and a sharp rise in CS in the early 2010s as big tech really started to take off. But, I can’t help but feel that there are probably not more people who used a balanced approach and found CS a better choice than all of the humanities. Also, it’s fair to notice science’s steep upwards growth, as STEM is perceived as safe and high-paying.

But really, this graph just goes to show the #1 focus of students as they gear up to enter the workforce — return on investment (ROI).

This is expected and reasonable, especially for those who are doing damage control after taking out copious amounts of debt. The 2010s revealed how expensive college can be, and how easy it is to get burnt by the “degree & debt cocktail”, so it makes sense for ROI to be prioritized.

Yet, it’s likely that the knee-jerk reaction has overcompensated, as they usually do. There’s just no way that CS careers provide the best balance of pay and interest for all these people, it’s clearly about ROI.

I’m not advocating for the humanities or shitting on CS, just highlighting a worrying imbalance. It’s not like this problem is limited to CS anyways.

Meaning that to fall into the prestige trap at the end of college is to maximize ROI over everything else, to sit down behind the wall and watch the shadows go by.

But why is this bad? Everybody’s getting their cheddar, who cares if they’re unhappy at work? It’s only 24% of their life anyways!

Aside from the job market of each industry just being a giant supply and demand function, with high-paying jobs guaranteed to pay lower salaries if everybody jumps on the boat.

Even if we ignore that leaving the cave gets harder as you get older, and those that enter unhappy chasing money likely won’t become substantially happier.

There’s still a major concern, which is the decision driver — to use measurements and quantitative means to measure ourselves against others with the hopes of being happy.

This paradigm breeds unhelpful habits; materialism, constant comparison to others, and unhappiness. Use LinkedIn for example. What started as a networking platform turned into a professional and politically-correct circle jerk. There are pretty much only two kinds of content:

Dopamine farmers writing way too much about being hired at [insert big-name company] which they probably only took for the name and to be perceived as better than their peers.

Weird facebook-style posts and companies thwapping themselves on the back at how wonderful, unique, and “different” they are.

All in all, it’s straight status games. It’s still a good tool to learn more about an industry and to network (when done properly) but that’s not the primary focus anymore. But, it’s not just annoying. It’s concerning, it’s depressing.

No, I’m not being dramatic here. Watching a huge chunk of graduates enter the workforce and active members of the workforce farm self-worth on social media because they didn’t build it themselves is bleak.

There’s an old adage that goes something like this:

If somebody is truly happy, they won’t brag or rub it in your face.

- Billy Trout, 2023

Although this sounds almost too simple to be true, it’s for good reason. To anybody living in a large city, have you ever met somebody who only has to capacity to talk about their job and their possessions? I actually had one guy show me his average-looking wallet in NYC only to tell me it was $700 and then followed by saying he likes that people don’t know it’s that much by looking at it (why would you tell me then?). It’s uncomfortable and we all know we don’t want to be that person. God knows why LinkedIn rewards this behavior, it’s the same principle, just wrapped differently.

Comparisons and over-measuring lead directly to materialism. Let’s work back to the wallet guy in the above paragraph. If you held me in above a thousand spiders and told me I had to tell you his correct reasoning for buying the wallet or you would drop me in the pit, it would go something like this:

Well, I actually have no idea what to do with my money. Buying things helps but I need to show them off to people and receive that fresh dopamine hit. That’s why I gave into the desire to tell Billy how much it was worth, he had to know because if he didn’t, I would get little pleasure from owning it.

Materialism is a product of monkey status games and has been running rampant for a good three decades now, especially ramped up over the past decade as social media has risen in popularity. Social media shows people — young and old — that money equals happiness as the most popular influencers are often showing their wealth and material possessions. It’s not so different from the earlier analogy of students recognizing that higher grades will give them more happiness. Both situations use ends as a predictor of happiness rather than means.

There’s overwhelming evidence of materialism’s rise (not that it’s needed, just go socialize and you’ll see).

Consider the continued rise of designer brands in 2022 — a bad year financially for everybody — wherein Chanel, Dior, and Gucci rose their brand values by 32%, 27%, and 23%. Looking into how these brands market themselves is valuable in determining why people purchase their products, as nobody is spending as much effort learning their customers’ motivations as they are. Here are some recent changes in designer logos:

Notice the logos’ over-simplification. Any luxurious-looking fonts are removed in favor of basic ones that ensure maximum readability. They prioritize making their brand name readable because it’s already recognizable. The most important piece of marketing for these brands is making sure that the brand name gets out there. Influencers and commoners alike do the rest of the work. It’s boring and takes some flavor away, but the flavor isn’t what sells, it’s the name. It’s the “yeah this is Balenciaga”.

Materialism isn’t just limited to designer brands. It also considers the way Americans handle their savings. Consider the meteoric rise (and fall) of Robinhood and crypto during the pandemic. Instead of Americans opting to save their newfound money, they decided to put it into high-risk speculative assets. Indicating that the small chance of “getting rich” was worth more than adding extra stability to their current lives. Once again, focusing on the ends instead of the means.

Overall, materialism is a problem but only insofar as any other symptom of disease would be. A 2011 study found that depression is linked to increased compulsive buying. Similarly, a 2020 study found that social media addiction is positively linked to materialism in adolescents.

I’m sure everybody has felt the shot of pleasure after buying something new, so using this as a quick fix for unhappiness shouldn’t be surprising. Those who were taught to measure their self-worth will combat their problems the only way they know how — by increasing their measurable metrics.

Suddenly, that 24% of hours unhappy becomes a lot scarier, and the money loses some of its value.

But how can our youth be expected to leave the cave? They weren’t taught to value alternate routes to happiness, and they didn’t gain independent thinking skills to value their individuality. Instead, they built their self-worth by measuring themselves off the shadows of others.

The prestige trap is what holds us inside the cave, chained up and letting something that was never real dictate our perception of reality and of ourselves.

Follow me on Twitter to stay updated here.

I’m diving into some of the stuff mentioned here deeper in the coming weeks, stuff like the appeal of trading/crypto, modern house design, and maybe LinkedIn but I feel like I already gave it a good rip.

Would you like to discuss this article for my podcast? I tried to direct message you on twiiter, but was unable. I'm @jimbostank on twitter. I'll tweet you