All Unique Maps Lead to the Same Destination

The Employee Factory II: Utilitarianism and Broken Feedback Loops in Schools

In the last installment of the Employee Factory series, I use Socrates to criticize what modern schools consider learning and discuss structural limitations teachers face that make this pseudo-learning the standard. It’s not critical to read the first installment, but it would make my philosophy clearer.

Although it may be difficult to relate to Julius Ceasar (unless of course, a dictator is reading this), you may have had a similar schooling experience to him. Take this recounting of one of his earliest memories:

When I was 5 years old, my mom always told me that happiness was the key to life. When I went to school, they asked me what I wanted to be when I grew up. I wrote down “happy”. They told me I didn’t understand the assignment.

Was he wrong? I mean technically he was but that’s under the assumption that the set of correct answers, was in fact correct. Sure, he also chose an adjective when all the answers were most likely nouns (what an idiot).

But, is there another purpose in life? Happiness is a bit too ambiguous and could lead to hedonism, so let’s say the goal of life is to feel fulfilled.

But what does it mean to be fulfilled? By definition, it means “to be happy or satisfied due to fully developing one’s abilities and character”. Notice that this definition implies fulfillment to have unique requirements for each individual, it’s not a one-size-fits-all.

It’s impossible to wander down to a pharmacy and purchase fulfillment pills (yet happy pills do exist, we’ll get to those later).

There’s no more obvious place that could prepare children for their unique journey to fulfillment than the place where they spend almost all of their waking hours — school. Yet, not much has changed since Julius’ time and our system punishes uniqueness instead of nourishing it.

The ideal student from elementary to university is the one who sits still, stays quiet, memorizes information and regurgitates when called upon, doesn’t speak out of turn, and doesn’t challenge the information being taught.

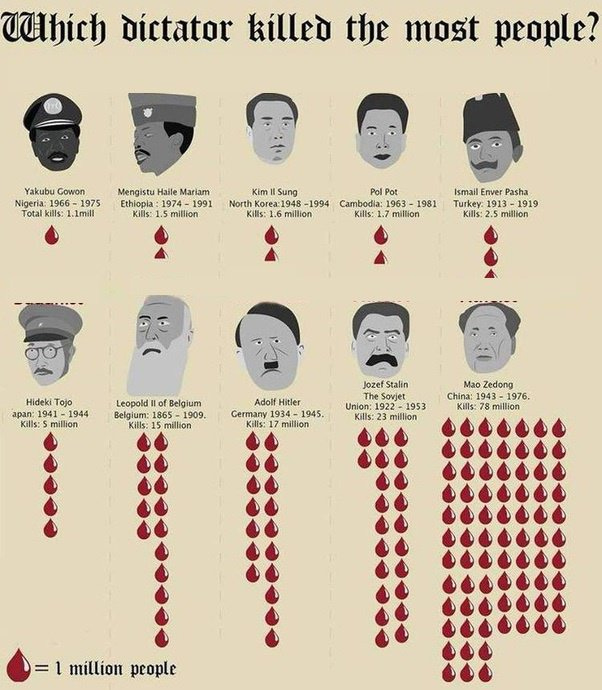

If we were to remove this pattern of behavior from schools and place it in Stalin’s Soviet Union, it would be the framework of an excellent comrade!

Stalin would get his citizens to obey through a questionable feedback loop, but a feedback loop nonetheless. It was truly simple, obey the state or get sent away to a place where the sun doesn’t shine. Of course, there was an angle of Stalin promising equality and extinguishing fascism, but anybody who believes this to be the primary driver of obedience has never felt fear.

So, as with all behavior, it is fair to assume that our schools give students a feedback loop in reaction to their obedient behavior. Thankfully, this feedback loop is more family-friendly, consisting of positive affirmations and praise. Encouraging students to continue to behave obediently as the feedback loop helps them build their self-image positively.

As mentioned earlier, Stalin would remove the disobedient from society, not just simply kill them immediately. He was a clever comrade, by removing them from society, it did not become a question of “obey or die” but rather an inquiry of “obey or be removed from your peers AND probably die”. This was likely intentional by Stalin and not from the warmness of his heart. By threatening removal, he was able to play on human’s innate need to be social and part of a community while removing the noble prospect of being a martyr. This increased obedience within communities as a whole since nobody wants to wear a Scarlet Letter.

Although not nearly as harsh, the negative feedback loop in schools often looks uncomfortably similar to Stalin’s. When a student colors outside of the lines (literally & metaphorically), they are removed from their peers. Sometimes this looks like detention after school, taking away time they would typically spend with friends. It can also look like being forced to sit alone in class or to step out of the classroom for the rest of the period. Regardless, ostracization is a primary repercussion for disobedient students in classrooms.

However, ostracization is not the only thing used to get students to behave. We’re also lucky enough to give students as young as 3 years old (wtf?) literal go-pills in amphetamines such as Adderall. I’m not joking, amphetamine—the active drug in Adderall, Vyvanse, Ritalin, etc.—was first developed for fighter jet pilots in WWI.

Parents are in such fear of their child being “left behind” or ostracized that they’ll give them fighter-jet pills, in what world is that not utterly insane?

Even if we ignore the long-term side effects such as dependency, weight loss, and a slew of heart issues. Students now have it affirmed internally that there is something wrong with them that is out of their hands. During a time when they build their self-image, this will hamper children throughout their entire life.

The irony is that kids don’t just pop out of the womb unable to focus, it’s mainly from external drivers. In fact, most behavioral disorders are issues of external stimuli, not genetics. Suggesting that the solution would be different external stimuli. But then again, it’s much easier to just give a kid a pill and tell ‘em to fly.

Although comparing a man who killed over 20 million people to the education system may feel apples-to-oranges, that’s because it is. But still, both are fruits. If we ignore intentions, we’ll find that both have the same end goal—conformity.

This is especially concerning in schools because bad behavior is so negatively correlated with test scores. Essentially suggesting that those who sit still, listen, practice, and memorize are the most likely to be successful. Thus, through searching for behavioral conformity, schools are truly aiming for intellectual conformity, which is measurable via test scores.

The last bit is the most concerning part. Especially in pre-university schooling, students primarily use test scores to determine their self-worth and what’s possible for them in the future. Yielding lasting effects, especially before high school when self-image is still being built rapidly through the mirrors of their surroundings.

Meaning that those who receive positive feedback loops will perceive themselves in a positive light. By being rewarded with praise for obedience and good memorization skills, students are likely to continue down this path to receive more praise, becoming a subconscious path to feeling good about themselves.

The opposite is true as well, where many who don’t score as well may feel discouraged in the future and suffer from lowered self-esteem. Low self-esteem can lead to pessimistic thoughts about the future, which hinders one’s ability to reach their potential.

It’s understandable why grades can be perceived to be a strong proxy for future success. There are not really any alternatives and it’s a supposed measure of how well somebody knows a certain topic. But they're not a measure of the ability to apply any of the knowledge in a real-world situation (more about this in the last installment).

So, students are forced to behave in a conforming manner to achieve good grades or to deal with being affirmed that they are not intelligent, making them become less optimistic about their future.

Often it’s out of students’ hands. If a student isn’t challenged, they’ll become disengaged in class. If a student doesn’t have a stable home, they may not try due to a lack of support. If a student has social issues in their classes, they may act out and in turn not apply themself.

Are any of these indicators fair enough to indirectly tell a student they shouldn’t be optimistic about their developing their abilities?

Those who don’t or can’t conform aren’t given the tools to nourish their abilities because the barometer is broken, leaking mercury down their throats.

Intentions are critical and the education system has its ideology rooted in utilitarianism. Conformity is used as an attempt to create the largest good for the largest number of people with the (limited) resources given. This is why outliers (both positive and negative) are removed instead of nourished, it would be a sin to disrupt the group. Plus, making an example is always a good way to keep people in line.

The created good is the idea that those who conform to the school’s style of learning and excel will receive good grades and in turn a “better” job. Obviously, this is important and the causation between strong grades and employment is clear to all. This relationship puts a lot of pressure on students and forces them to conform behaviorally and ideologically as schools hold all the leverage.

Leading them to act out of fear of failure rather than a desire to develop their own unique abilities and character.

Meaning the feedback loop is still broken for those who conform. It’s still a “follow the leader” approach in which students are not determining what their interests are, they’re just studying what they are told and waiting for positive feedback. Thus, the information taught is only learned insofar as it helps students build their self-worth and feel more optimistic about their future job prospects.

The problem with following the leader is that eventually, the leader disappears, the real world begins, and young adults begin to wander following a North Star that no longer shines.

Unlike the real North Star, an individual’s North Star must be unique under the definition of fulfillment. But how do we find our own? By nourishing creativity because our thought processes and ideas are the most unique thing we have.

Consider a 2014 study conducted in Sweden:

Creative professionals had a reduced likelihood of having schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, unipolar depression, anxiety disorders, alcohol or drug abuse, autism, or ADHD.

Even when removing professionals from the equation, creative activities are rapidly becoming an effective form of therapy.

Crazy right? Almost as if external stimuli can solve a problem caused by external stimuli, I wonder what nutcase said that. Further, is it not fair to assume that flexing our creative muscles can allow us to take our self-image back from our beholders?

Yet, creative subjects—English, Philosophy, Arts—are neglected across the board by students and schools due to them being non-quantifiable.

Art has been around for almost 30,000 years and calculus has only been with us for 450. Obviously, neither is more important for everybody and this just goes to show how silly trying to play god and quantify things can be.

Yet, students have been taught that their education is solely a prerequisite to a job—insofar as a prerequisite for survival—so they don’t understand the importance of class which isn’t easily quantifiable as it doesn’t have the same feedback loop. School funding largely comes from standardized exams in which although writing is a portion of it, it’s not creative writing and consists of either vocab or comprehension.

I don’t think students or schools are to blame for this, it’s really a top-down problem and it largely falls out of both’s hands. I genuinely believe most teachers are doing the best they can with the cards dealt.

Still, creative classes are essential to helping students learn more about themselves and enable them to express their own uniqueness. Nobody can write the same story as another, nobody can make the same piece of art without trying to, and anything created from nothing will always be inherently unique to its creator.

Similarly, nobody can have the same path to fulfillment.

That’s what makes rejecting outliers without attempting to understand the root of their behavior to be so dangerous. In doing so, schools suggest anything different from the pack to be bad, decreasing anybody’s chances of exploring their creativity.

If those who do conform aren’t taught the value of qualitative things and outliers are punished for acting on their own devices, how is it reasonable to assume that anybody would find value in their creativity? If nobody is able to appreciate their own creativity, how would they learn to appreciate and understand their own individuality? If nobody is in touch with their own individuality, how can they be expected to find their unique path to fulfillment?

Then what happens? Will we suffer the same fate as Caesar? Assassinated by his own peers in the Theatre of Pompey, as they hoped to destroy his dictatorship and create the greatest good for all.

But remember, Augustus soon rose to replace Caesar and his death was all for nought.

FYI I’m not anti-school, anti-grades, or one of the “motivational” crackpots who tell kids on social media that the easy way out is the best way. I’m advocating for balance and for everybody to take a chill pill, not meth’s cousin.

The next installment in the series will be out over the next couple of weeks and will revolve around the futility of prestige. Follow me on Twitter to stay up to date here.

As always, comments are appreciated and I’d love to hear viewpoints different from mine.

Great read, echoes some of the arguments put forth by the late John Taylor Gatto in his books (I have only read Weapons of Mass Instruction).

While fulfillment is a worthier pursuit, I think both happiness and fulfillment are fleeting emotions and therefore inappropriate as potential purposes of life. I cannot say that I have a more appropriate purpose to provide, but given our social nature I think a possible purpose is to be in the service of others. This could be on a local (family, friends, neighbours) or global (via the arts, science, business) scale. This does not contradict your statement about individuality as there are many ways in which we can be of service to others.

I think the main (academic) purpose of schooling should be to develop our abilities to think and communicate as these are the foundational skills from which all other skills can be developed.

With regards to confirmity, I think this is somewhat inevitable when working at the scale of modern schools. Students spend more time with peers than teachers even in a classroom setting. Given that schooling take place at such formative years the environment has such a significant part to play. Creativity flourishes in non-judgemental environments where learners feel safe to make mistakes. Peers tend to be much more judgemental than teachers and therefore conformity ensues with or without the negative and positive feedback loops - it is just a matter of whose conformity. More often than not, the peers are given preference over adults.

Talk to most educators and you will find that the biggest factor in a child's learning is the parent. Where open parents are present members in the child's life, you find more prosperous learners. The student's creative interests can be facilitated best by parents.

These were just different thoughts that entered my mind while reading this article. Looking forward to reading the final installment shortly.